India’s Moonshot

On 2nd October 2018, Prime Minister Modi announced a grand vision of creating the “one world, one sun, one grid” network. This mega project, once completed, will create a massive single grid network that will power every continent through day and night by transferring the power of the afternoon sun almost instantaneously to any part of the world. Sterlite Power echoed this vision with an idea championing the development of the IEG (Intercontinental Electricity Grid) that proposed a connector between Asia and Africa using a submarine HVDC network. The proposed connector offers a practical, simple yet challenging & futuristic solution to bring this vision to life.

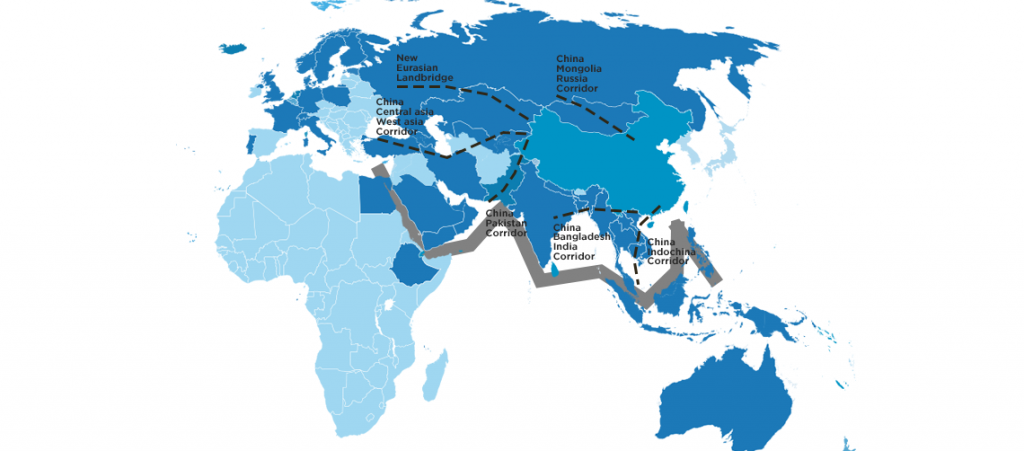

Kerala’s legendary Muziris port, heart of the Spice Route, vanished off the grid 3,000 years ago. It was once an established spice trade centre which enabled pepper from the vines of Malabar to find its way to Egypt, the transcontinental Asian-African country. This trade route coexisted with China’s Silk Road, trading routes established during the Han Dynasty, which linked regions of the ancient world in commerce. The spice and silk routes enabled India and China to become formidable powers of the time. That was then. Fast forward to the twenty first century. In 2017, China launched its modern reprise of the Silk Road trading route — the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative: a grand infrastructure project to connect nearly 70 countries across three to four continents by building a massive network of roads, ports, railways, bridges and gas pipelines using the ancient Silk Road blueprint.

OBOR underscores China’s ambition to create a dominant geopolitical position in Asia leveraging its infrastructural heft. It is now India’s turn to reprise the Spice Route with an intercontinental electricity grid (IEG), a super intercontinental power grid connecting India and Africa. It would be a monumental project aimed at smoothening out the inequality of power generation and demand. Indeed, a grand project with as much infrastructural heft as OBOR.

Why IEG?

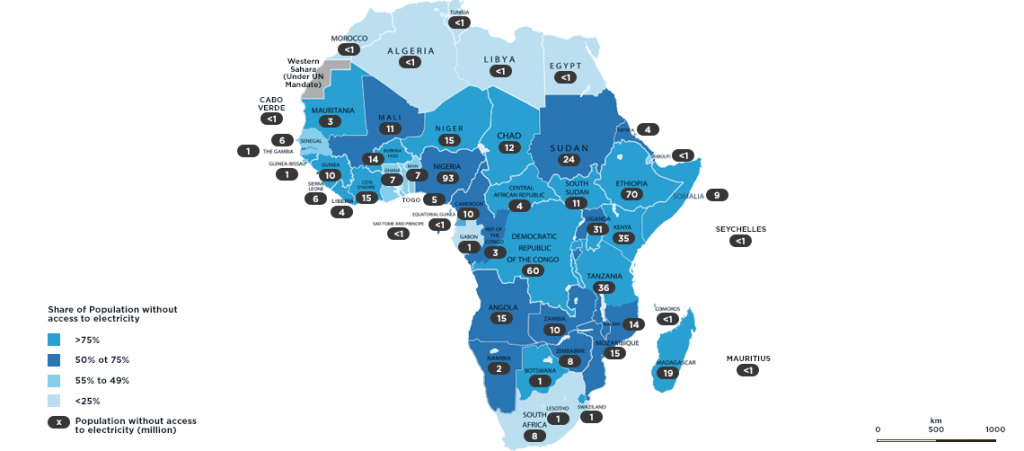

According to the World Energy Outlook Report 2017, only 43 per cent of the population in sub-Saharan Africa has access to electricity. The African governments are working closely to improve their installed capacity to 253 GW by 2030 but that requires huge investment. Besides, it does not solve the demand problem – if proportional electricity demand does not go up as anticipated, that massive investment would come to naught.

As India pushes towards a low carbon transition by expanding its renewable energy capacity (it plans to double its renewable capacity by 2022), its demand profile will shift. Advanced renewable economies find that their power demand peaks for four hours from 5 p.m. to 9 p.m. This is also the time when renewable power, especially solar, is less available. This leads to the infamous duck curve — a timing imbalance between peak demand and renewable energy production. This peak demand, at say, 6 p.m. would be 3.30 p.m. in East Africa and with the sun shining bright, it can support the Indian demand. What is more, the Indian grid can also transfer power back to the African countries during their peak time when these countries are short of solar power.

IEG: Compelling facts

IEG could be a 1,000 MW HVDC link connecting the two continents through either of the two routes:

- Kochi-Djibouti (Kochi-Lakshadweep-Socotra-Djibouti) (total length 3,600 km): An average depth of 2,700 metres undersea, and with specifications of 1,000 MW, +/-1,100 kV, a rough estimate would place the cost of the entire HVDC link between $8 billion and $10 billion. The longest length of undersea cable will be between Lakshadweep and Socotra at 2,080 km. The biggest hurdle in this option would be the development of HVDC subsea cable technology and laying of a subsea cable for 2,080 km.

- Porbandar-Djibouti (Porbandar-Al Hadd- Murad-Djibouti) (total length 3,100 km): This option reduces the total length of the undersea cable to 1,000 km and reduces the complexity of laying subsea cables across the Arabian Sea. The estimated cost of this line is $4 billion-$5 billion.

There are live, and inspiring, examples where such a massive project has reaped impressive dividends. The NorNed HVDC link (580 km in length, 700 MW /450 kV HVDC) that connects Norway’s hydro assets with the Netherlands’ predominantly fossil fuel powered grid is a case in point. The subsea cable has helped both nations reduce their collective carbon dioxide emissions by 1.7 million tonnes annually while avoiding blackouts, optimising the cost of electricity and increasing the stability of the grid. Likewise, the IEG will allow both continents to benefit from grid stability, afford a better energy mix, reduce carbon emissions and optimise their energy spending.

Is IEG illusory? Not at all. Demanding and gruelling, yes. And not cheap. But it could just be the panacea needed to solve, or at least mitigate, endemic power problems of the two regions. Indeed, IEG could be India’s moonshot — a project that could help us overcome critical bottlenecks and spur a whole new industry with cutting-edge technology.

Besides, the IEG will be in line with our Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s dream of creating regional connectivity through robust infrastructure while emphasising the tenets of openness, equality and sovereignty.

It’s an idea whose time has come.

Pratik Agarwal, Chief Executive Officer, Sterlite Power Transmission Limited

Read more: Indian Infrastructure

Please wait...

Please wait...